written by Lee Marks

Lee Marks is the CEO of Break the Silence UK Charity

https://www.breakthesilence.org.uk

Exploring the Experiences of Male Victims Reporting Domestic Abuse and the Impact of Police Responses on Reporting Rates.

Dissertation submitted as part requirement for the Master’s Degree

Understanding Domestic and Sexual Violence

Trigger Warning

“This is the full version of Lee Marks paper. Unlike the abridged version, this has not been adapted so will contain language and terms that maybe offensive to some. The CEO of JHM felt it was right to keep the paper in it’s fuller form as when we have the right knowledge available to us, we are then able to confront, challenge from a position of knowledge instead of ignorance. Inside this article you will read accounts of men that may become a potential trigger, if this is the case please click the speech bubble and there will be someone you can talk too, to help you understand why it was a trigger. Due to the nature of Lee Mark’s work and experience in this field of working with Male victims of abuse, the risk of potential triggers is considered to be minimal.”

Abstract

Within the UK, domestic abuse is considered a gendered crime, disproportionately affecting female victims more than male victims. Resources available for those that suffer abuse has always been predominantly aimed at females, run by feminist organisations who appear to set the narrative on domestic abuse across all sectors. This gendered narrative leaves one third of all victims unable to access support and fearful of speaking out as their experiences does not fit the accepted narrative.

This research explores male victims’ experiences of reporting their experiences to the police and how this interaction affects and impacts their experience as a victim of domestic abuse with a view to answering a very simple question. When it comes to male victims of domestic abuse, are the police a help or a hinderance?

The comprehensive literature review uncovered concerns around gender stereotyping, provision of service and the impact of claiming domestic abuse is a gendered crime. Alongside this, 8 semi-structured interviews were recorded via Microsoft Teams, transcribed and further analysed using thematic analysis. Emerging themes again showed gender bias as a concern, along with neutrality by officers, communication and respect. These findings supported and furthered previous research in this area, suggesting that male victims were subjected to unfair treatment by the police, with all experiences being reported as negative.

Ethical Considerations

When applying for ethical clearance to conduct my research, I was sure that the questions that I wished to pose to those participating in the research would not cause any problems. This was because having worked with victims of abuse for many years, I am very experienced in speaking sensitively about their experiences and how to signpost to further support. This proved to be the case in obtaining the ethical clearance that I required, however, had there been any recommendations to change these, I would have had ample time to do this before conducting my research. When preparing my questions, I had already examined a number of other research articles of a similar nature that had already been conducted to gain an idea of what had already been examined, and where the significant gaps were that I aimed to address.

One of the identified ethical considerations that I had to take into account was the current relationship status of those wishing to participate as if they were still within their abusive relationships, there would have been an elevated level of risk when conducting the interviews due to the possibility of either being overheard or their perpetrator returning mid-interview. This was addressed by adding the stipulation that all selected to be involved had to be no longer within the relationship which minimised any risk that they would face. As a researcher there is no measurable way to completely ensure that the criterion had been met, other than to rely on the honesty of those participants involved.

The only other potential risk that I needed to consider was the emotional impact on the participant due to the nature of the subject matter. This was addressed by providing information of professional agencies such as Mankind Initiative, Men’s Advice Line, Galop, Men’s Aid Ireland and Abused Men in Scotland that could support them if this was the case when providing the initial information, before the interview began and again on completion of the interview. I decided to use these bigger national organisations sue to the limited numbers of more regional services that provide support for men. The participants were also reminded that they could cease the interview at any point, should the need arise. For myself as the researcher, I have years of working within the domestic abuse field and am used to hearing potentially distressing narratives, as well as managing their distress. It was recognised though that despite this experience, there could be a potential need for support. Structure was put in place to be able to access my research supervisor as well as accessing other professional resources to debrief following any potential difficult disclosure.

Limitations

Due to the nature of how organisations operate and the need to access gatekeepers for permission to discuss clients and work with professionals, I knew it would be difficult to obtain many interviews with professionals. Although this is understandable, my research would have benefitted from more of an understanding from a professional’s perspective. However, the wealth of data gathered from the male victims themselves more than makes up for the shortfall in professionals. The main limitation that I faced was the small number of men that I had the opportunity to interview as they could effectively share their own personal perspectives on their experience, but could not speak for all male victims. Despite this, and the fact they were all white heterosexual males, all my participants were all of different age groups and from different geographical areas, meaning the data was from a wide area and not focused on one geographical area.

Male Perpetrated Domestic Abuse

For most people, when they hear the words domestic violence or physical violence of any kind within a relationship, they will picture a woman being assaulted by a man (Marks, 2021). But it hasn’t always been that way. Feminists have fought hard for to have the experiences of women recognised, citing gender inequality as one of the primary factors contributing to intimate partner violence against women (Dobash and Dobash, 2004). This process has seen reforms in law that has provided legal protection including orders such as non-molestation orders, occupation orders, domestic violence protection notice and orders, but also the development of community-based services, refuge services and a wealth of education around understanding and prevention. This work has led to the feminist framework that depicts males as perpetrators of domestic abuse and females as the victims (Dobash et al, 1990; Nicolson, 2019; Walker, 1989; Walker et al, 2020). This should never be discounted as statistically, the number of women that are murdered as a result of domestic abuse continue to be high (Allen et al, 2020) and the level of physical and sexual injuries they suffer that require hospital treatment does remain higher than male victims (Elvey, Mason and Whittaker, 2021)

Due to the achievement of the feminist movement, violence against women by their male partner is now recognised globally as a significant social problem. This is recognised on a daily basis by services such as the NHS, police and social services with various programmes and interventions seeking to help female victims seeking assistance against the violent episodes they face (Dobash and Dobash, 2004; Hester et al, 2020).

When looking at the behaviours that women face within intimate partner violence, fear is one of the key themes. Not just the fear they face from their partner due to men’s physical advantages of size and strength (Hamby and Jackson, 2010), but also fear of leaving, of the unknown, but on the reverse side of this, fear is also a motivating factor when women do eventually flee the relationship (Scheffer, Lindgren and Renck, 2008). And women have reason to fear their violent partners as research indicates that female victims of intimate partner violence are more likely to sustain serious physical injuries, some suggest this could be up to seven times that a man faces, and experience long term physical and psychological consequences of the abuse (Allen et al, 2020; Coker et al, 2000; Coker et al 2002; Hester et al, 2020; Straus and Stith, 1995). The recommendation based on all the academic research within this area suggests that the first priority in services for victims and in prevention and control must continue to be directed towards assaults by men.

Physical and psychological side-effects are another aspect that needs to be considered as the impact of living within a controlling relationship is still underestimated. When it comes to intimate partner homicides, before 1990’s female victims were not that dissimilar in levels to men. However, this has changed over the years since then with around 70% of the victims after 1990 being women killed by their male partners or to look at this another way, three women killed for every man (Saunders and Browne, 2000). This trend continues today, and although 2020 saw the lowest numbers of women killed by men since 2009, 110 women were killed by men (Allen et al, 2020). 56 of these women were killed using a weapon, 24 from strangulation and 14 through direct physical assaults with hitting, kicking and stamping. This in itself shows why men are seen to be more able to injure women (Seelau and Seelau, 2005, Bates 2019) and why male-perpetrated violence against women is taken more seriously than female-perpetrated acts against men (Hamby and Jackson, 2010; Allen and Bradley, 2018; Seelau, Seelau and Poorman, 2003).

There is a need to understand what causes male perpetrators to act out in this way, and if examined from a feminist perspective of IPV then men’s possessiveness and jealousy, their sense of right to punish for perceived wrongdoing, maintaining a position of authority and a need to control are cited as reasons for this behaviour (Block et al, 2000; Dobash & Dobash, 1992; Goetting, 1996; Wilson, Daly, & Daniele,

1995). Other conclusions would suggest the concept of ‘hegemony masculinity’ which is a term used to refer to men engaging in practices that stabilise gender dominance (Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005) further supported by the work of Marks (2021) who states “males within the room say ‘if that was me, she’d get the back of my hand and that would be that’”.

Female Perpetrated Domestic Abuse

In contrast to the abuse suffered by women, historically there has been what can only be described as a ‘conspiratorial silence’ (Dobash and Dobash, 1992) around the conversation of women’s violence towards men. However, since the turn of the century there has been more academic research conducted to complement the small amount of research prior to this, examining female perpetrated IPV and the reasons behind this.

From this research arose increasing evidence that suggested that women commit IPV on the same level, or in some cases more, than men (Archer, 2000; Cook, 1998; Fiebert, 1997; Melton and Belknap, 2003; Straus, 1997) and certainly when it came to adolescents, this was consistently the case (Arriaga and Foshee, 2004; Hickman, Jaycox and Aronoff, 2004; Lichter and McCloskey, 2004; Munoz-Rivas et al, 2007; Schwartz, O’Leary and Kendziora, 1997; Williams, Ghandour and Kub, 2008)

Research indicates that the most common types of physical abuse experienced by men is that of slapping, kicking, biting, scratching and choking (Drijber, Reijnders and Ceelen, 2013; Hines, Brown and Dunning, 2007). There is a perception that physical assaults of this kind, do not often end with the male victims being seriously hurt. Yet there is evidence that in over 50% of cases where female perpetrators use physical aggression, they will use some kind of a weapon (Drijber, Reijnders and Ceelen, 2013) such as a knife or stiletto heel (Marks, 2021) which will increase the risk of harm to a male victim significantly. Research suggests that contrary to belief, over 80% of male victims are injured by their female perpetrator (Hines and Douglas, 2010) with in excess of 30% suffering serious injury such as a broken bone (Mankind, 2020).

In the journal article ‘How Many Silence Are There?’ by Brooks et al (2020, page 5397), one man shares his experiences.

“She was hitting me up in the face area with her fists and like I said, she’s not weak. I think that’s a misconception with a lot of guys. I’ve notice that they think women are weak and there are a lot of tough women out there, a lot of them. She cracked me in the jaw and she cracked me in the ribs. I still got really bad ribs because she hit me, like three times, and I wouldn’t lift my hands to defend myself like that. I wanted to. If it was a guy, it’s a different situation, you can defend yourself so I kept on taking these hits.”

Another method of abuse that seems to be commonly used by female perpetrators is that of sleep deprivation as it leaves the victim in a vulnerable position, and potentially others if they are employed (Williams, 2007). This method is used as a form of punishment and torture, hence why some that have experienced this would define it as ‘living with intimate terrorism’. Sleep deprivation not only leads to exhaustion and then on to illness, as our bodies need sleep to keep functioning, but due to the impact it can also lead to economic abuse as victims may find themselves facing disciplinary proceedings at work for being late or making mistakes (Pearson, 1997).

The final commonly referenced method of abuse is that of false allegations. This can be the threat of them or the actual use of them. In Bates (2020, page 18) article ‘Walking on Eggshells’, Bates referenced a victim’s experience that highlights this.

“I have never attacked her or fought back at all. I have tried to restrain her at times to prevent her from attacking me. She would then show me bruises a couple of days later and tell me that she could report me to the police for assault and that they would believe her story.”

The most common use of false allegations is in regards to children, which for male victims is perhaps the most distressing of their abusive experiences, especially if these false allegations lead to parental alienation from their child (Gardner, 1999). Allegations of this type are efforts by perpetrators to manipulate the legal system and family courts to the detriment of their victim, commonly seen with men. This not only has a long-lasting effect on fathers and their wellbeing, but this separation also has an impact on the children’s behaviour and emotional wellbeing (Stadelmann et al, 2010).

In relation to domestic homicide, there is much suggestion within academic research that women are more likely to use violence as a means of self-defence in an attempt to stop their partner from harming them or their children or to prevent an attack they believe to be imminent (Dugan et al, 1999; Jurik and Winn, 1990). These can be viewed as excuses however, judges and juries often believe that homicides in these cases are in self-defence or that there are strong mitigating circumstances, which is supported by the fact that between 2017 and 2019, of the 89 men that were killed by their intimate partner, only 9 were charged with murder (ONS, 2020).

Although self-defence is cited as a reason to explain homicide, many women do not cite it as a reason for violent and abusive behaviour against their partner. What they do cite are motives such as jealousy, retaliation and control and dominance (Felson and Messner, 2000; Follingstad et al, 1991). As can clearly be seen is that the motivating factors are similar to those suggested by the feminist movement for men’s reasons for abuse and the suggestion that half of all violent arguments are initiated by women, how can the suggested patriarchal system be deemed the cause for domestic abuse?

Violence perpetrated by women is less significant in terms of frequency, severity and consequences, and therefore clearly minimised and judged less likely to need any kind of intervention (Hine, Bates and Wallace, 2022; Hine, Noku and Bates, 2022; Sorenson and Taylor, 2005). Whilst conviction rates against men show it is treated far more harshly when perpetrated by a man (Dobash and Dobash, 2004; Feather, 1996; Hamby and Jackson, 2010).

What is clear from the academic literature available is that male victims experience a similar level of fear to that reported by women as a result of IPV (Hines, Brown and

Dunning, 2007). What is more is that there is evidence of clear links between men’s fear from their partner to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression and suicidal ideation (Randle and Graham, 2011), and it is recognised that suicide most effects men as a demographic.

The Case Against Defining Domestic Abuse as a Gendered Crime

Over the years, organisations have run a number of social experiments where societal reactions were tested on the basis of gender with domestic abuse. In all cases with female victims, members of the public interjected, however, when the victim was male the incident was ignored or laughed at (Marks, 2021). How is this acceptable and how has this come to be the norm, especially when there is parity between males and females in cases of minor violence towards an intimate partner (Brogden and Nijhar, 2004).

As far back as the 1980’s, some academic literature claimed that the feminist stance on domestic abuse being a gendered crime was a falsely framed issue and that the truth was that men were just as victimised as women. This was always countered with women’s need to use violence as a means of self-defence (Mackay et al, 2018; McNeely and Robinson-Simpson, 1987; Saunders, 1988). This sems to have been the standpoint that society has taken as on the most part as legislators and policy makers have accepted the issue of domestic abuse as a problem of men’s violence towards women (Dobash and Dobash, 2004). Attitudes in society are influenced by societal constructed gender perceptions of both masculinity and femininity, depicting men as strong and aggressive, and women as vulnerable and in need of protection (Bates, 2019; Seelau, Seelau and Poorman, 2003). By accepting these gender perceptions, as a society we are disposed to dismiss women’s violence as inconsistent with that of a perpetrator of domestic abuse due to the imbalances of power between men and women (McCarthy, Hagan and Woodward, 1999).

Academics looking at the concept of domestic abuse being recognised as a ‘gendered crime’ have identified a number of flaws within the literature. Some of these reasons being that female violence is equal to or more frequent to men’s violence against intimate partners (Feibert, 1998; Whitaker et al, 2007), IPV being due to psychological reasons, not to do with a ‘patriarchal society’ (Babcock et al, 2000; Fergusson, Horwood and Ridder, 2005; Follingstad et al, 1991; HoltzworthMunroe and Stuart, 1994), that men as well as women could be injured as a result of IPV (Hines, Brown and Dunning, 2007), both men and women have reported the use of violence for control within an intimate relationship (Felson and Messner, 2000; Follingstad et al, 1991) and coercive control is perpetrated at similar rates by both men and women (Bates, Graham-Kevan and Archer, 2014; Carney and Barner, 2012). Yet despite all the findings, there is still the strong focus on female victims (Bates, 2020) and it is suggested that this gender framing could explain why male victims fail to recognise themselves as being victims, being recognised as victims rather than perpetrators by the wider society and their ability to receive the support they need (Huntley et al, 2019). The wider impact of this is that men do not report their experiences by their female partners, therefore male victims are not recognised as priority for resources and funding and practically all domestic abuse training provided to statutory organisations such as the police, NHS and local authorities is gendered in nature, focussing on women as victims and men as perpetrators. This creates in itself a culture of ignorance about men’s ability to be a victim of domestic abuse (Brooks, 2006).

Men’s Reasons for Not Disclosing

Within the current literature, a reoccurring pattern is that men are consistently less likely to seek help than women (Addis and Mahalik, 2003), some reference it being 3 three times less likely to speak out (Mankind, 2020). What is it that makes this the case? Research into reasons why men don’t disclose their abuse focuses on the fear of not being taken seriously (Drijber, Reijnders and Ceelen, 2013), not believing service that can help are available (Tsui, 2014) or as most of the services sit within female-based organisations that they would be unhelpful (Machado, Hines and Matos, 2016) for a man seeking help with abuse from a female partner. These organisations cannot be apportioned blame for this as in most cases, male services are attached to the female contract and the female-based services expected to deliver them.

One type of IPV that is a real fear for male victims is that of legal or administrative abuse, where the perpetrator manipulates the system through false allegations. The threat of false allegations or the threat of parental alienation are common factors that arise. There is evidence within research that some abusive females threaten to report their partners for assaults that they have never committed, creating feelings of fear and powerlessness as they knew they were unlikely to be believed (Avieli, 2021; George, 1994; Mazeh and Widrig, 2016; Sarantakos, 2004).

Literature suggests that societal male gender roles have their part to play in this, as men are seen as self-reliant and stoic, some would describe it as the good old fashioned ‘stiff upper lip’ and help-seeking is seen as the complete opposite of this (Vogel et al, 2011). This is a major obstacle when it comes to seeking help for domestic abuse, meaning many will mask the issues or do what they can to avoid the problem (Tsui, 2014), and could also go some way to explain why male victims struggle to identify as a victim (Machado, Hines and Matos, 2016). The concept of masculinity has also been drawn on when trying to understand abuse against men (Corbally, 2015; Morgan and Wells, 2016), with many men identifying with feelings of shame and embarrassment, or feeling emasculated and set to face public ridicule for not meeting the gender role expectations placed on them (Hogan, Clarke and Ward, 2021), and society does still judge people on what happens to them.

We know that the status of ‘victim’ doesn’t apply to men and women equally and this will affect help-seeking decisions made by male victims (Seelau, Seelau and Poorman, 2003; Bates, 2019). This decision is also affected by what is portrayed in the media, where 99% of all features and stories are in relation to a male on female abuse. This lack of recognition from those that could influence societies beliefs that anyone can suffer domestic abuse instead compounds the lack of recognition in society, leaving male victims feeling that they have no one to talk to as they won’t be believed (Brooks, 2006).

There is clearly a need to change this dominant narrative about gender roles and instead address all victims’ barriers to seeking help (Bates, 2019)

Exploring Help Seeking Experiences of Male Victims of Domestic Abuse

For all victims of domestic abuse, friends and family are quite often the preferred choice as a help-seeking option (Bates and Graham-Kevan, 2016; Chabot et al, 2009) and this makes their reactions particularly important. The reactions of family and friends could be key to if the victim of abuse then goes on to seek more formal sources of help such as statutory agencies. For men, they experience shame and embarrassment which is similar to the experiences of women, but with the added barrier caused by societal stigma of being a male victim. A supportive reaction can help to mediate through these feelings, they can’t remove them, but a supportive attitude can diminish these negative feelings (Tsui, 2014; Bates, 2019). It is also important to realise that even with family and friends, they are likely to have been influenced by wider societal perceptions such as men are strong, women are weak and it is possible that on an unconscious level these perceptions can be evident (Bates et al, 2018).

It is a simple fact that men are often met with a level of suspicion or not being believed when trying to seek help for domestic abuse. Respect, who operate the Men’s Advice Line, created a toolkit for working with male victims of domestic abuse (Respect, 2019) which includes an assessment to deem if the male victim is indeed a victim or if they are a perpetrator trying to use the system against their female partner, a practice not currently used when assessing female victims for support. This can lead to secondary victimisation and male victims feeling as though they are on trial for seeking help and support.

Police officers have been found to hold gender stereotypes that influence how they react and respond to incidents of domestic abuse, with men reporting that they have felt blamed by the police for their abuse (Hine, Bates and Wallace, 2022; Stewart and Maddren, 1997). This is down to the gendered training that is provided to the police as an organisation and that until recently, at any incident of domestic disturbance the male would be arrested or removed in line with what was ‘positive action’ police arrest procedures (James, 2015) and this has contributed to a lack of trust in the police with male victims, reflected in the reporting levels (Mankind, 2020).

In Bates (2019) article ‘No One Would Ever Believe Me’ one man interviewed stated

“I reported her to the Police on one occasion and was asked what I had done to deserve the beating, I told them I had done nothing at all, to which they told me that was unlikely and it was probably something I had done or said”.

This is also echoed in Marks (2021) book ‘Break the Silence’ where he depicts the numerous incidents and injuries suffered by a male victim of domestic abuse which resulted in him being taken to a place of safety.

For many men, the lack of recognition of male victimisation, leaves them without support (Hogan, Clarke and Ward, 2021) and organisations that do support them, such as the Mankind Initiative help-line consistently receive calls from men that have experienced injury yet have been the one that has been arrested (Brooks, 2006).

Summary

As you will see within the next chapter, the data that I have collected during the course of my research has managed to fully answer my research question “Police – help or hinderance? Exploring the experiences of male victims reporting domestic abuse and the impact of police responses on reporting rates”. The data gained also poses recommendations on changes that need to be made to the current methods employed when investigating the report of this crime, which will be explored further within the discussion chapter.

Findings

The interviews were conducted with six male survivors aged between thirty and sixty-two and two professionals that had many years of experience working with male victims and survivors via Microsoft Teams. All the survivors were from heterosexual relationships and all lived in various parts of the United Kingdom at the time of their abuse. The men that were interviewed shared not only their experiences of reporting domestic abuse to the police, but also their experiences of the abuse they suffered, adding context to the results.

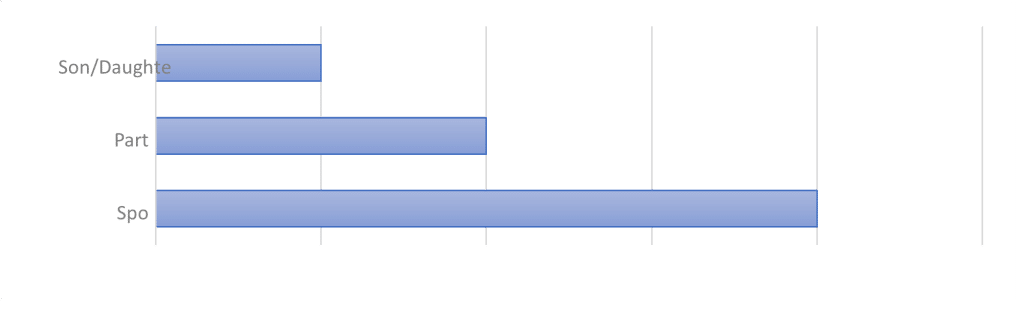

All of the men experienced domestic abuse from their immediate partner, being either their spouse or partner, and one of the men also experienced abuse from their adult children.

Of all the men involved, all but one described the types of physical abuse they had suffered during the course of their relationships.

“I remember one incident on a summer morning when I came down stairs very happy and my ex-wife was in the kitchen. This wasn’t normal as usually she would be in bed until 2pm in the afternoon and stay in her pyjamas all day. I don’t know what instigated it but she attacked me with a knife which resulted in my hands being cut to pieces. This wasn’t the only time she attacked me with a weapon, she has done so many times, including with a vase which left me with issues with my coordination and a time she smashed a glass in my face.”

“Over our relationship I’ve had many times that I have had my clothes ripped, my hair pulled out, deep scratches on my chest and face from her fingernails that were so deep that they bled. But that was just the basic shit she would do. On bad nights she would use weapons like a television and a counter-top fridge that she threw at me.”

“I decide that I just had to end things as she had started to become physically violent. What I mean by physically violent is hitting, punching, slapping, but she would know where to hit. She never hit my face for example, she would hit my balls. She also seemed to enjoy biting my penis, my testicles, the inside of my thighs, sometimes it was so bad that the site where she bit would go black. There were also incidents of eye gouging, which with her nails, they would go deep into my eye socket.”

All of the men involved disclosed incidents of both emotional and psychological abuse during the interviews, that impacted them just as much as the physical abuse.

“I think my earliest memory of the change in her behaviour was when she started accusing me of having an affair, she would demand to check my phone and social media looking for anything that she could use against me.” “For me personally, the extent of what I suffered was verbal abuse from my now ex-wife. She used to put me down a lot, saying that I was useless at everything and that all I was good for was bringing money into the house for her to spend, and that even with that, it was not good enough as she needed more.”

“She insinuated that I wasn’t valued within my job and that I should leave and find something that was better paid. I ended up working away as an effort to avoid her actually. I can remember looking in estate agent’s windows looking for a place to rent, thinking ‘this is crazy, I own this house and I’m thinking of moving out just to stay away from her’.”

When using thematic analysis to review the data, it became clear that the main themes that ran through all of the interviews were gender, respect, neutrality and communication.

Gender

Gender was the most common theme throughout all of the interviews that I conducted, this was from both survivors and professionals. The views shared were varied between their own thoughts, actions and conclusions made based on interactions with officers during their involvement.

Comments made by the police towards the men involved in this study featured prominently in the data, the two examples below highlighting why male victims believe that gender remains a big issue when the police are investigating domestic abuse allegations.

“Take one occasion, I called them after being choked by my ex-wife, they finally came several hours later and found me at the end of the street, sat on the corner as I was too afraid to go home. Hours, it took them after an assault and their excuse was that they were short staffed and that my life wasn’t at risk. I asked them why they perceived I wasn’t at risk, and they said because I was a man.”

The one copper actually said to me “let me get this straight, you want me to believe that a woman half your size, smashed a television over your head? Get real”

“The sergeant that took me from one town to the other to collect my car said to me that he had had this happen to a male colleague too in the past. He recommended that I thought about this and to learn from experience.”

Alongside the experiences of the male survivors, the professionals involved in the interviews mirrored comments similar to that the men reported themselves. In one case that was heard at MARAC, when discussing a case within a gay relationship “the detective inspector of the police was incredibly dismissive and questioned why I would bring this case to discussion in the first place, saying that as it was two blokes surely, they could ‘just fight it out and have a pint afterwards.’”

The men recognised that this type of dialogue is common from the police and that as a man “you’re expected to show that stiff upper lip and get on with things”. The data also showed that in situations where the police were called to an incident or when a counter allegation was made, they felt that gender played its role again regarding the actions of the police.

“I think on the number of times they were called out when I had been assaulted, they spent more time talking to her than they did me, making sure that she was alright despite my injuries. I don’t think that was appropriate as I was clearly the victim. It was as though their go to response was to focus on the female in the situation.”

All the men reported that in situations where they had disclosed the abuse they had experienced to the police, which was followed by a counter allegation being made, and that they would find themselves arrested whilst the investigation into their report seemed to disappear. In one case, which was similar to many of the others, the male victim said:

“I talked to them about all the times she had assaulted me and even told them to check their records of the times they had come to our home, but they weren’t interested.”

These experiences of verbal or perceived gender-bias clearly had an impact on what these men thought of how the police react to male victims of domestic abuse, stating that “the system isn’t set up to help men”, that “women are the protected gender by the police” and that if they would advise a man to report abuse, all would say “I’d advise any man not to.” This general consensus was summed up by one of the participants who said:

“There needs to be a change in the way police deal with incidents as in the case of false allegations being made, for a man, when that happens, your life is over. It doesn’t matter if it’s true or false, as a man you’ll be offered a caution or you’ll be taken through a court process and weather found guilty or not, that stigma will follow him around for the rest of his life as his name has been in the press. The simple fact is that men are terrified of the police and what will happen to them. You’ve got the whole believe all women movement, but where does that leave us men that are victims of false allegations? It is really, really frightening to be a man. There is definitely a bias against men.”

Gender was a common theme amongst the participants within the research and this is consistent with the lack of acceptance that men can be victims of domestic abuse (McCarrick, Davis-McCabe and Hirst-Winthrop, 2016) found within other academic research material.

Until more recent times, domestic abuse or interpersonal violence was viewed as an issue that was faced exclusively by women (Nowinski and Bowen, 2011) and that violence perpetrated by women was as a result of violence resistance or situational couple violence (Johnson, 2008). The issue faced by male victims when looking at this theory is that it delegitimises their experiences and the data collected reinforces that this does clearly discourage men from seeking professional help (Lysova and Dim, 2022).

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 (HM Government, 2021) was promised to be a gender-neutral approach to addressing the issue of domestic abuse, however many believe that this in itself fell a long way short by not allowing much in the way of evidence to be delivered by professional organisations supporting male victims (Mankind Initiative, 2021). This was followed by the update on the Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls strategy (HM Government, 2021) and the released position statement on male victims of crimes considered in the cross-Government strategy on ending Violence Against Women and Girls (HM Government, 2019), again diminishing the abuse male victims suffer by making them a subsection in the Violence Against Women and Girls strategy.

The data gathered by the participants shows that all experienced bias that they believed was based on gender and that they believed that men were not believed, in most cases they were viewed with suspicion. The same experiences can be seen within other current academic material supporting the data within this research (Lysova and Dim; 2022, Brooks et al, 2020; Dim, 2021). Research shows that this underlying belief that professionals, including police, hold gender bias about who is likely to be the victim (Lysova et al, 2020) is a major factor preventing men from coming forward and receiving the support that they should.

Respect

Being believed when reporting incidents of domestic abuse is paramount for a victim, regardless of their gender, and this falls under respect. “If a victim can’t be taken seriously and police can’t see the risk people are facing then society is well and truly broken.” In some of the interviews conducted, it was stated that the police were respectful when investigating counter allegations as it was believed that “they were trying to get some kind of a confession”, but “as soon as I told them that it was me that was being assaulted, that respect went out of the window”. This lack of respect clearly left many of the men that had gone to the police for help and support feel like they were “treated like a common criminal”.

Respect is more than just what is said though, and this was reiterated time and time again within the data with the words “showed absolutely no interest” featuring in all interviews” and another stated “the officer was lent back in this chair, hands behind his head and it was clear he wasn’t paying a blind bit of attention to me. They just don’t give a shit.” Even in situations raised where complaints procedures were followed, there was a lack of respect shown towards these male victims.

This complaint went to the IPCC and proved my case, but still never received any resemblance of an apology for their actions. Does that sound like respect to you?”

Male victims of domestic abuse face the possibility of being re-traumatised by not being believed and being treated with a lack of respect, and this does impact on their perceptions of the police.

The men involved within the research reported to not being treated fairly or with respect from the police throughout all stages of investigations and there were predominantly negative attitudes towards police reflected within the data.

As with the data gathered in this research, there are numerous accounts within academia of negative responses from other male victims, such as being turned away or not being listened to (Machado et al, 2016; Walker et al, 2019) through to experiences of being humiliated and laughed at (Nowinski and Bowen, 2011; George, 2002; Bates, 2020; Lysova et al, 2020)

Alongside this we had the experiences shared within the research that the police would fail to attend an incident when reported from a man, which again is supported by accounts of a similar nature within another piece of research by Machado et al (2016).

HMICFRS (2019) recognised that police were failing to record adequate statements within 45% of cases reviewed, that police are sometimes too slow in getting to domestic abuse incidents and that there was a need to seek victim feedback from incidents that they attend. This research can clearly contribute to this and shows the feelings of a subsection of male victims and their experiences when reporting their abuse to police.

Neutrality

Neutrality, or the lack of, sits closely with the theme of gender, but does deserve to be looked at in its own right as again it was a prominent theme, with all of the men involved in this study do not believe that the police act in a neutral manner when investigating incidents with male victims of domestic abuse. There was evidence throughout the data of experiences of charges or threats of charges brought against them, despite evidence existing to the contrary.

“There was another time that I had to call them to the house after I was assaulted and even though I was the victim, they said they were going to remove me from the home instead of her. I pointed at her and asked “How, after what she has clearly done to me?” and was told that if I looked at her like that again, I would be arrested. Weigh that up in your mind, man gives a look, woman commits assault and it’s the man threatened with arrest.”

“They ended up offering me a caution on the basis that my actions were in fact common assault. I couldn’t believe that they weren’t interested in any of my evidence and the duty solicitor said that effectively I had admitted it.”

On more than one of these situations within the data, when the men involved asked to speak to a specialist domestic abuse officer, they were “refused permission to speak with an officer from that unit.” This sort of behaviour was again echoed through the data gained from professionals who said that “fear of not being believed”, of being “seen as the perpetrator” and the “impact this has on their future” are all major barriers to men reporting to the police. They too had witnessed incidents where men were met with “dismissive attitudes”, “asked what they did to deserve it” and told to “stop wasting police time.”

There was a recognition within the data that their female perpetrators lived with “an air of invincibility” due to the lack of neutrality or action against them when investigating incidents of domestic abuse. Despite the evidence and the visible injuries, for most of the men, their reports to the police never progressed any further.

“My ex-wife actually told me on many occasions that the interview was nothing but an informal chat, no statements were ever taken and she was never charged with any of the injuries I sustained.”

One thing that was apparent from all the data that was collected around neutrality was that they recognised that this wasn’t just something that is inclusive just to the police and that this is something that goes right through the legal system, especially when considering sentencing for domestic homicide.

“The majority of men that kill their female partner get murder; the overwhelming majority of women that kill their male partner get manslaughter. Where’s the justice in that?”

Participants within the research suggested that there needs to be more of a neutrality in the way that police respond to domestic abuse, with many reporting that they were often faced with false or counter allegations, leaving them being addressed as the perpetrator and their initial complaint/report being ignored.

The criminal justice system and the way domestic abuse is discussed within this field tends to view females as victims and males as perpetrators or aggressors (Laskey, Bates and Taylor, 2019) which is reflected within the data, along with the suggestion that female perpetrators take advantage of this fact. Research does suggest that women are just as likely to start an assault or violence (Dim, 2021; Gondolf, 2011), with the perpetrators in 70% of cases of nonreciprocal violence in heterosexual relationships being women (Whitaker et al, 207). Research in this area also reveals that motives for such incidents were anger and coercive control (Langhinrichsen – Rohling et al, 2012), similar to the motives reportedly behind men’s violence. However, it is clear that this contradicts what is being reported by feminist organisations (Jasinski, Blumenstein and Morgan, 2014) and the current prevailing societal norms (Nowinski and Bowen, 2011), where many men, including those within this research believing that it is more acceptable for a woman to hit a man, than it is for a man to hit a woman (Wright, 2016; Sorenson and Taylor, 2005). In the article by Walker et al (2019) there is a quote from a male victim that reportedly been made by a police officer that said:

“We get hundreds of cases of DV a week and they are mostly women; they are our priority.”

When evaluating the data from the research and other academic research and articles, there is a similar theme through all around the subject of false allegations being made against the male victims. When looking at this subject on the Women’s Aid website under their myths page, it is claimed that false allegations about domestic abuse are extremely rare, quoting prosecution rates as the source of data for this claim (Women’s Aid, 2021). However, from the data in this research and from other academic studies, that most male victims feel that when a false allegation is made against them, their disclosures of being a victim of domestic abuse is either ignored (McCarrick, 2015) or not followed through with the priority seemly being on the female’s disclosure. HMICFRS (2019) recognise that there is an importance to arrest the offender in cases of domestic abuse, however it does seem that there is a reluctance to arrest female perpetrators (Dutton and Nicholls, 2005), especially when faced with allegations from both parties. This is reflected in the fact that in cases where men have contacted the police because their partner was violent, they were more likely to be arrested (Lysova and Dim, 2022; Douglas and Hines, 2011).

It is believed that this stems from the College of Policing 2017 ‘Positive Action’ police arrest procedures, where it clearly stated that even if the woman is the aggressor, it would still be the man that was arrested or removed first (James, 2015). Although this has since changed, it is still clear that this is still the routine being followed in so many areas because as with any change in procedure, it takes time to take effect.

Communication

In life, one of the key skills that we need to learn is that of communication, as without this we would not be able to request the things we need or respond to such requests. This is the same for victims of domestic abuse who have been subjected to power and control from their partners, and for the majority of the time having no say or understanding in what they have been subjected to.

Communication, and lack of communication was another theme that was prominent throughout the data. As referred to earlier, the way that officers involved in the investigations communicate directly with the victims, has a massive impact and when done incorrectly or unprofessionally this can lead to re-traumatisation. Within the data, men have referred to officers not really listening to what is being said or referring to the incidents as being “tit for tat”, minimising their experience, as well as making diagnosis that clearly, they are not qualified to make.

“I remember this clearly, he said ‘people are psychologically damaged by abuse, but you’re not’.”

I would go as far as saying they aren’t interviews, they are interrogations.

You’ll tell them things and two seconds later it’s forgotten as it doesn’t fit their view on the situation.”

Bur from the data gathered, it isn’t just about the direct communication, but also the lack of communication from the police that impacted on the men interviewed. Only one of the men reported that he had been kept up to date from the officers involved in the investigation of his case, the others report being “kept in the dark”. In most of the cases discussed, the requests that they themselves were making for any updates again were going unanswered, with no response forthcoming.

“I asked for an explanation and got nothing so I decided to make a complaint. This resulted in more contempt from the police who weren’t even willing to provide me with the names of the officer involved for my complaint, it’s like they closed ranks.”

“This went on, the case was dropped, and the court then ordered them to pay costs to me. But this wasn’t what I was after, I didn’t want money, I wanted answers from the police to the questions that I had asked and why they had failed to do this.”

These experiences weren’t only restricted to the men interviewed as the professionals that provided data commented that communication with the police wasn’t a strong point, especially when providing information for further support, and how this then impacts them and the relationships with the victims that they try to support.

“These were incompetently completed by officers who gave us none of the details meaning that we would have to call the victim and complete it all over again. Can you imagine the impact of this when we called to gain those details? “I’ve already disclosed this, why are you asking again?” I couldn’t really say that they had given me nothing could I? If you give a male victim the feeling that the police aren’t listening, why would they believe that you would be any different?”

Finally, we look at the theme of communication and in particular how male victims feel the police communicate with them. There is clearly comparative evidence within the research data and the other reported experiences of this within academic research with male victims repeatedly reporting that they are showed little to no interest when reporting their abuse to police (McCarrick, 2015), being talked down to or even in some cases laughed at or ridiculed about their experiences (Machado et al, 2016; Walker et al, 2020). Throughout all of the research in this area, there are a number of references to being ‘treated like a guilty perpetrator’ or ‘common criminal’ (McCarrick, Davis-McCabe and Hirst-Winthrop, 2015).

Summary

For the male survivors involved in this research, the perceived lack of respect may be a by-product of the gendered approach to domestic abuse and the stereotyping that goes alongside this where as they are perceived as perpetrators. You cannot ignore that all involved had negative experiences of reporting to the police that has left them with no confidence in them or any other male victim approaching police to make a disclosure, and that their experiences have left them living in fear of the perpetrator and the police equally.

Although the data collection was from a small cohort of men within a much wider picture, it is quite damning that from their experiences they answered the question posed by my research, are police a help or a hinderance, with all categorically stating that police are a hinderance.

Recommendations

Based on the data gained within the research and from all other academia on this subject matter, this section focuses on recommendations for improvement within policing, as one of the targeted outcomes was to explore what male victims thought needed to change or improve to encourage and support male victims to approach the police. Within the Policing Vision 2025 document (NPCC, 2021), it states that their mission is:

“To make communities safer by upholding the law fairly and firmly; preventing crime and antisocial behaviour; keeping the peace; protecting and reassuring communities; investigating crime and bringing offenders to justice.”

When looking at this, it needs to be recognised that all the men involved within this research expressed a level of fear and distrust in the police at varying levels, some stating they fear the police will come for them and some even facing nightmares.

“This was followed up by me having some absolutely terrifying nightmares, where the police were framing me for murder. I spent a good year absolutely petrified of the police. I used to park my car a good half a mile from home, walk across fields and sit in darkness as I was sure they were going to come back. On some occasions I would sit for an hour or two before I would feel comfortable enough to turn the lights on. Any time I saw or heard a police car, I was sure they were coming for me.”

“Even now, nearly 10 years later, I was walking up the street here with the woman I am now married to and a police car was driving slowly toward us and I felt that rush of terror again that they were coming to get me.” This fear being described by the male victims within the data is echoed by a number of other sources within academia, particularly around the fear of being arrested if they engaged in self-defence when being assaulted or if they contacted the police themselves to make a disclosure (Dim, 2021; Bates, 2020)

Training, Procedures and Signposting

All the participants, both survivors and professionals, expressed that there is a need for a change in the training provided around domestic abuse, away from the gendered narrative to a more encompassing of all victims training. One of the professionals expressed concern that the current DA Matters training police undertake through Safe Lives only gives a passing mention to men and focuses on the ‘gendered narrative’ of female victim, male perpetrator.

“Firstly, we need to see a stop in the gendered training delivered to the police.

I know for fact that the training they get gives a passing mention to male and LGBT victims but focuses on male perpetrators and female victims. If we are only training officers in this way, is there any wonder they have such a blinkered belief system and can’t accept male victims?”

When it comes to training, it was recommended by the majority of the participants and within other academic research that there is a need to move away from the ‘traditional feminist perspective’ of domestic abuse and more towards a societal view that addresses the potential for both men and women to be both victims and perpetrators of domestic abuse (Machado et al, 2016; Tsui, Cheung and Leung, 2010). There is suggestion that this should include male victims as well as female victims having the opportunity to discuss their lived experience and a consideration for the creation of specialist roles for working with male victims. It is believed that this would “stop hindering men being able to make disclosures.”

All the participants within the research agreed that the current system of policing does not work as there is a total focus on violence against women and girls to the detriment of male victims. This is supported within other research and suggests that the gender paradigm and the focus on violence against women and girls creates institutional barriers prevent men from seeking and receiving help from the police (Lysova and Dim, 2022; Machado et al, 2016; Bates, 2020).

“The police seem to have jumped on the gendered narrative that is portrayed by feminist organisations such as women’s aid. I’m not in any way trying to diminish the progress made by these organisations as this was so needed, and I know society is focused on violence against women and girls and rightfully so, but this shouldn’t be at the detriment of men and boys.” It was recommended that if the police want to gain the trust of innocent male victims, they would “need to demonstrate more compassion and empathy” as well as “improving their overall integrity” in an effort to “follow through to the last letter of the law” regardless of gender, instead of “cherry picking which cases are most worthy of their time.”

The final recommendation that was made was for it to become routine for police to provide details of organisations that can provide support to male victims as this rarely, if ever, happens. It is standard practice to do this for female victims, so why not male victims.

“They never once offered me any information of services that could support me, I literally had to beg them before they eventually provided it. I was literally in tears of desperation at this stage.”

Consideration to the findings

The research explored the male survivors’ experiences of domestic abuse, with a specific focus on their experiences of reporting the abuse that they had been subjected to, to the police. It also aimed to explore the impact that these interactions had on their experiences. It revealed what can only be described as significant failings within the police force, such as gender bias shown against male victims, unprofessional conduct, behaviour and communication and failings to investigate fully the abuse suffered by male victims when counter or false allegations are made against them by their female partner or perpetrator. The participants involved within the research were invited to answer the question “police – help or hinderance?” within the semi-structured interviews, with both survivors and professionals unanimously indicating that the police were a hinderance with their approach to male victims of domestic abuse.

The research was corroborated by the existing literature within this research field, concluding that despite the vast period of time that is covered by the literature, no changes have been made and the impact of the police on male victims creates a professional barrier to them being able to seek further help from the services that are there to protect them. The literature also corroborated the experiences the participants had of perceived gender-bias, suggesting that this isn’t just perceived by male victims and in fact is happening, and the lack of neutrality being shown when investigating these incidents. The perspectives of the police were on the whole negative, with recommendations for improvement focused on the need for gender-neutral training to be provided, including the use of male and female survivors to give real life accounts of what they experienced and a need to move away from the current gendered narrative, supported by feminist theory, to a more societal view that recognises all victims regardless of their gender.

The aims and objectives of this research focused around understanding the ‘lived experience’ of the male victims in regards to their experiences of domestic abuse and of reporting to the police. The aims and objectives of this research were clearly met as all participants identified that categorically current practice within the police force does not support male victims when it comes to speaking out and receiving support they require. They also identified changes in which they felt would allow male victims to have faith within the system and that those they interact with would have an understanding of their experiences, without this being of detriment to female victims. There was a real sense of all victims being supported and no focus only on male victims, showing compassion towards all victims within their position. This research does contribute to, and builds on the existing literature within this field as it continues to show the inadequacies within the system that have been prevalent for in excess of ten years of academic research, with little to no suggestion that this has been addressed. This research also adds the ‘survivors voice’ into the data that already exists, adding another dimension for consideration in future research projects.

With the identified objectives within the research, it had been an objective to explore not only the survivors’ experiences and their impact, but also the experiences and views of professionals from within the field. Despite my connections within the domestic abuse community, I found that it was much more difficult to obtain professionals to take part in the research. I recognised that this could have been difficult due to the fact that the majority of professional contacts do still work within domestic abuse organisations, many of them feminist organisations, and it was possibly felt by senior management that involvement within research into male victims went against the ethos of their service. I do not have evidence that this was the case, but the lack of responses from professionals limited my research in this area to only two professionals. This doesn’t give a wide data pool of information from professional organisations, however, the data received was significant within the findings.

Conclusion and Personal Reflection

The overall aim of this research explores the extent in which police involvement with male victims of domestic abuse helps or hinders their ability not only to report their perpetrator, but to have the ability to move forward in recovery after their abuse. In order to achieve this, there were two clear objectives that were identified:

- To explore the experiences of male survivors of domestic abuse by means of semi-structured interviews to outline their individual reporting experiences and the impact these experiences had on them.

- To explore the interactions and experiences of professionals who work, or have worked, with male victims of domestic abuse in regard to reporting their abuse to the police.

Domestic abuse has affected not only myself as a male victim, but others within my family quite significantly and this has been the drive in everything I do. I have experienced very similar abuse to that what was described by the participants, yet had no experience of reporting this to the police, as I unfortunately was one of the many men that do not recognise abusive behaviours for what they are. And it is this that motivated me not only to publish my own book to support male victims, but also to register on this Master’s course to further my knowledge and understanding, to be able to better support all victims of domestic abuse.

Conducting this research has been one of the biggest challenges of my life, taking many long hours and late nights. But it has been rewarding as it has improved my knowledge and understanding of male victims, and given me an insight into what male victims want from support. I will continue my work with male victims and following this research, I am committed to continue to challenge the gender-bias within the system and ensure that male victims do not continue to be invisible to society. I can only hope that we all acknowledge and listen to all victims and survivors, and ensure that with the recommended changes discussed within the research, no victim is ever denied justice for the crimes perpetrated towards them through domestic abuse.